Motion in One Dimension

Introduction

The study of the motion of objects is known as mechanics. Mechanics can be divided into two parts: kinematics and dynamics. Kinematics describes how objects move, while dynamics describes why they move in the first place. We will only look at one dimensional kinematics in this section.

Physical Quantities

In order to solve a kinematics problem, we need to use a coordinate system. This coordinate system forms our frame of reference. In order to perform measurements, we must have a frame of reference.

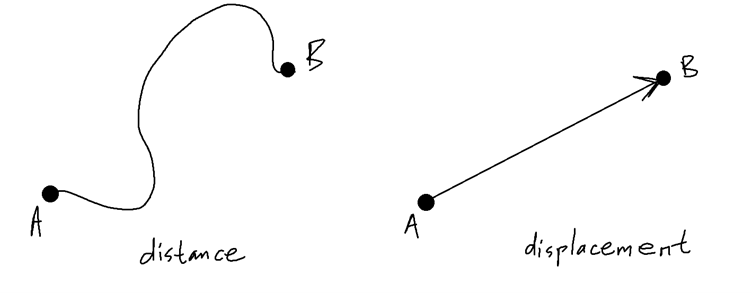

Distance is the amount of space through which an object has moved to get from one point to another point in our coordinate system. Distance is a scalar quantity. This means that it is described only in terms of its magnitude, i.e. "the amount of it". We measure distance in meters (m)

Displacement is the straight line distance between two points. In Euclidean geometry, a straight line is the shortest distance between two points. We can think of displacement as the change in position of an object. If an object moves from point A and it returns to point A, its net displacement is zero. However, the distance travelled is not necessarily zero (it could have moved in a circle. However, we will not discuss circular motion).

There is a direction associated with displacement. For example, we need to specify if the object has moved from point A to point B, or from point B to point A. Depending on how we've oriented our coordinate system, the direction of the displacement determines whether it is positive or negative. Since magnitude and direction are needed to describe displacement, it is a vector. Since we'll only be discussing one dimensional motion, we'll not go into too much detail about vector mathematics. That will be discussed when we consider two dimensional motion.

The average speed of an object is the time it takes for the object to travel a certain distance, \begin{equation*} \text{average speed} = \frac{\text{distance travelled}}{\text{time taken}} \end{equation*}

Since distance is a scalar quantity, it follows that speed is also a scalar quantity. There is no direction associated with speed. Velocity, on the other hand, is a vector quantity. Velocity is the rate of change of position, or "how quickly the position of the object has changed", \begin{equation*} \text{velocity} = \frac{\text{displacement}}{\text{time}}. \end{equation*}

We can write the definition of average velocity in the x-direction as \begin{equation*} v_{ave} = \frac{x_2 - x_1}{t_2-t_1} = \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta t}, \end{equation*} where the $\Delta$ symbol reads as "the change in". Thus, the equation above reads as "the average velocity is equal to the change in displacement over the change in time". Since time is measured in seconds (s), velocity and speed are measured in meters per second ($m.s^{-1}$ or m/s).

Symbolically, we normally use $\vec{x}$ or $\vec{y}$ to represent the displacement. Some texts use $\vec{s}$ or $\vec{r}$. $\vec{r}$ is especially common when dealing with polar or spherical coordinates. The arrow on top of the symbol specifies that the quantity is a vector

I will use $x$ when describing motion in the x-direction (horizontal), and $y$ when describing motion in the y-direction (vertical). The $x$'s and $y$'s are often not written in vector form in one dimensional kinematics, since the motion is confined to one dimension only. For instance, an object moving along the x-axis is constrained to move either in the negative or positive x-direction. There are no $y$ or $z$ components to its motion.

In general, a three dimensional vector will have three components, i.e. an $x$, $y$, and $z$ component. When speaking about displacement in general, I will use $\vec{s}$, where $\vec{s} = (x, y, z)$.

Working with average velocities is not always particularly useful, since it doesn't give us an accurate description of how the particle was moving at a given moment in time. For instance, a particle could be moving very fast for a period of time, then slow down for a bit, then move in the opposite direction, and then speed up again intensely until it reaches its destination. I'm sure we can agree that the motion just described would not be best understood in terms of an average.

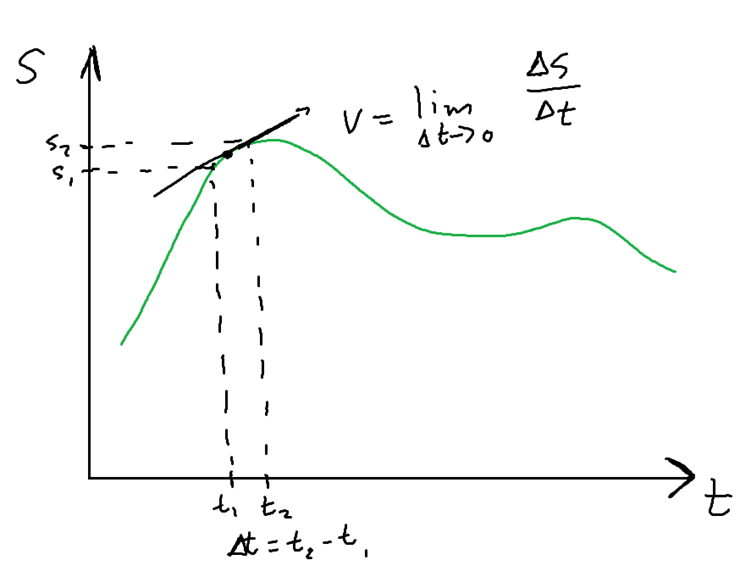

This leads us to wonder how the velocity at a specific moment in time can be determined. This velocity is known as the instantaneous velocity. We can obtain the instantaneous velocity of a particle from its displacement vs time graph.

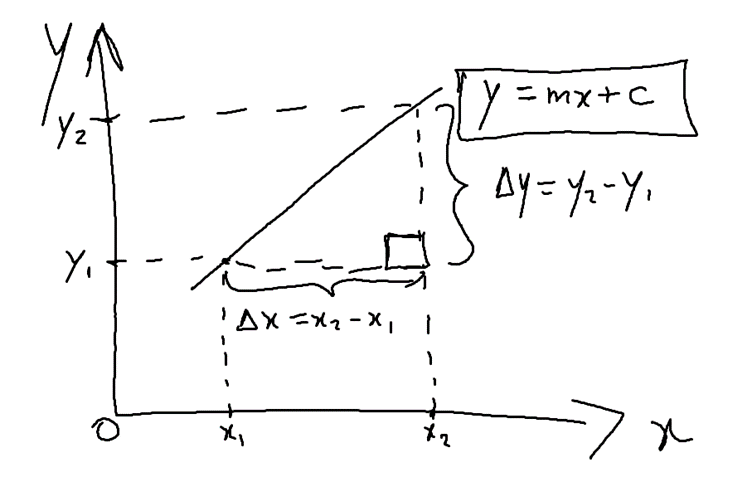

For a straight line in a coordinate system where the horizontal axis is the x-axis and the vertical axis is the y-axis, the gradient (or slope) of the straight line gives us the rate at which the y values change as x changes. It is a measure of "the rate of change of y with respect to x". \begin{equation} \text{gradient (or slope)} = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}. \end{equation}

If the y-axis represents the displacement, and the x-axis represents the time, then the gradient, which is now the rate of change of displacement with respect to time, gives us the velocity! But what happens if we don't have a straight line? What happens if we have a curve?

In order to get the gradient (or slope) of a curve at a point, we consider a tiny interval around the x-value of the curve. In our displacement vs time scenario, we consider a tiny interval between times $t_1$ and $t_2$. The position at time $t_1$ is $s_1$, and the displacement at time $t_2$ is $s_2$. Geometrically, this time interval is so small that the piece of the curve in this interval is approximately straight. The tinier the interval, the straighter the piece of the curve. We then calculate the gradient (or slope) of this approximately straight line.

If the time interval is infinitesimally small, we say that its limit is approaching zero. In the limit as $\Delta t$ tends to zero, we can calculate the instantaneous velocity of the particle. Mathematically, we have \begin{equation*} \vec{v} = \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0} \frac{\Delta \vec{s}}{\Delta t} = \frac{d \vec{s}}{dt}. \end{equation*} The notation, $\frac{d \vec{s}}{dt}$, comes from differential calculus and can be read as "the derivative of displacement with respect to time". The derivative of a function tells us the rate at which the function's y-values are changing as the x-values change.

Next, we consider what happens as the velocity of a particle changes. Using a similar line of reasoning as above, we now introduce acceleration, the rate of change of velocity with respect to time. The acceleration of a particle tells us if the particle is going faster, slower, or moving at a constant speed and direction. Since acceleration depends on the change in velocity, which is a vector, it follows then that acceleration is also a vector. \begin{equation*} \vec{a}_\text{ave} = \frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t}. \end{equation*}

Since acceleration gives us the change in velocity with respect to time, it is measured in meters per second per second ($m.s^{-2}$).

An object moving at a constant speed in the same direction has an acceleration of zero. When an object's acceleration is non-zero and it is moving in a straight line, then we are dealing with uniform acceleration. Many of the equations we shall soon derive are used to describe uniformly accelerated motion. We also have a mathematical definition for instantaneous acceleration, \begin{equation} \vec{a} = \lim_{\Delta t \rightarrow 0} \frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t} = \frac{d \vec{v}}{dt}. \end{equation}

Equations of Motion

Let us now use the definitions from above to derive some useful equations. Consider an object that's moving in a straight line with constant acceleration in the time interval $t_i$ to $t_f$ (let us use the subscript "i" for initial, and "f" for final). Its velocity at time $t_f$ is denoted by $v_f$, and its velocity at time $t_i$ is denoted by $v_i$. From the definition of average acceleration, we have \begin{align*} \vec{a} &= \frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t} \\ &= \frac{\vec{v}_f - \vec{v}_i}{t_f - t_i} \\ \implies \vec{a}(t_f - t_i) &= \vec{v}_f - \vec{v}_i. \end{align*} We can then write an equation to get the final velocity of particle moving with constant acceleration, \begin{equation} \vec{v}_f = \vec{v}_i + \vec{a}(t_f - t_i) \qquad \text{(constant acceleration)}. \end{equation} For convenience, let us set $t_i = 0$, and $t_f = t$. So equation (3) can be rewritten as \begin{equation} \vec{v}_f = \vec{v}_i + \vec{a}t \qquad \text{(constant acceleration)}. \end{equation} For constant acceleration, the velocity changes uniformly, so the average velocity would be the midpoint between the final and initial velocities, i.e. \begin{equation} \vec{v}_\text{ave} = \frac{1}{2}\left(\vec{v}_f + \vec{v}_i \right) \qquad \text{(constant acceleration)}. \end{equation} What would the position of a particle be if it travels with a constant acceleration for a certain time interval? We know that the average velocity is defined as \begin{align*} \vec{v}_\text{ave} &= \frac{\vec{x}_f - \vec{x}_i}{t} \\ \implies \vec{v}_\text{ave}t &= \vec{x}_f - \vec{x}_i \\ \implies \vec{x}_f &= \vec{x}_i + \vec{v}_\text{ave}t \end{align*} Substituting equation (5) in place of the average velocity, we get \begin{equation*} \vec{x}_f = \vec{x}_i + \frac{1}{2}\left(\vec{v}_f + \vec{v}_i \right)t, \end{equation*} and then substituting the expression for $\vec{v}_f$ from equation (4), we have \begin{align*} \vec{x}_f &= \vec{x}_i + \frac{1}{2}\left(\vec{v}_i + \vec{a}t + \vec{v}_i \right)t \\ &= \vec{x}_i + \frac{1}{2}\left(2\vec{v}_i + \vec{a}t\right)t. \end{align*} After expanding the right hand side, we get \begin{equation} \vec{x}_f = \vec{x}_i + \vec{v}_it + \frac{1}{2}\vec{a}t^2 \qquad \text{(constant acceleration)}. \end{equation} Equation (6) is very important and will be used quite often. Let us derive one more equation of motion. If we don't have the time, and would like to calculate the final velocity, then we can manipulate equation (4) as follows, \begin{align*} \vec{v}_f &= \vec{v}_i + \vec{a}t \\ \implies \vec{a}t &= \vec{v}_f - \vec{v}_i \\ \implies t &= \frac{\vec{v}_f - \vec{v}_i}{\vec{a}}. \end{align*} Let's plug the above expression for time into the average velocity equation, i.e. \begin{align*} \vec{x}_f &= \vec{x}_i + \vec{v}_\text{ave}t \\ &= \vec{x}_i + \vec{v}_\text{ave}\left(\frac{\vec{v}_f - \vec{v}_i}{\vec{a}}\right) \\ &= \vec{x}_i + \left(\frac{\vec{v}_f + \vec{v}_i}{2} \right)\left(\frac{\vec{v}_f - \vec{v}_i}{\vec{a}}\right) \qquad \text{(from eq (5))} \\ &= \vec{x}_i + \frac{||\vec{v}_f||^2 - ||\vec{v}_i||^2}{2 \vec{a}} \\ \implies \vec{x}_f - \vec{x}_i &= \frac{||\vec{v}_f||^2 - ||\vec{v}_i||^2}{2 \vec{a}} \\ \implies 2 \vec{a}(\vec{x}_f - \vec{x}_i) &= ||\vec{v}_f||^2 - ||\vec{v}_i||^2, \\ \end{align*} and we thus get \begin{equation} ||\vec{v}_f||^2 = ||\vec{v}_i||^2 + 2 \vec{a}(\vec{x}_f - \vec{x}_i). \end{equation} If you are not comfortable with the vector notation, then we can instead express equation (7) like this: \begin{equation} v_f^2 = v_i^2 + 2a(x_f - x_i). \end{equation} Please remember to use the appropriate sign depending on how your coordinate has been oriented, i.e. up is positive, down is negative; and to the right is positive, to the left is negative.

Vertical Projectile Motion

Galileo Galilei discovered (sometime in the 17th century) that the speed of falling bodies increases as they fall. This means that there is some uniform acceleration that is pulling bodies downward.

This quantity, known as acceleration due to gravity, is mathematically denoted as $g$. Its value varies depending on geographic location. However, for our purposes, we'll use $ g = 9.8m.s^{-2}$. Since gravity always acts downwardly, this value is negative (assuming that the orientation of your coordinate system has positive for up and negative for down).

The motion of objects in an upward or downward direction is called vertical projectile motion. The object will experience a downward acceleration even if its moving upwards. This downward acceleration eventually brings the object to rest. This occurs when the object has reached its maximum height. After that, the object begins falling to the ground.

When gravity is the only force acting on a falling object, we say that the object is in free fall. For vertical projectile motion, equation (6) can be written as \begin{equation} y_f = y_i + v_it - \frac{1}{2}gt^2 \qquad \text{(constant acceleration due to gravity)}, \end{equation} where $a = g = 9.8m.s^{-2}$.

Worked Examples

1. A stone is thrown vertically upward and reaches a vertical height of $2.8m$. How long was it in the air before returning to the ground?

Solution

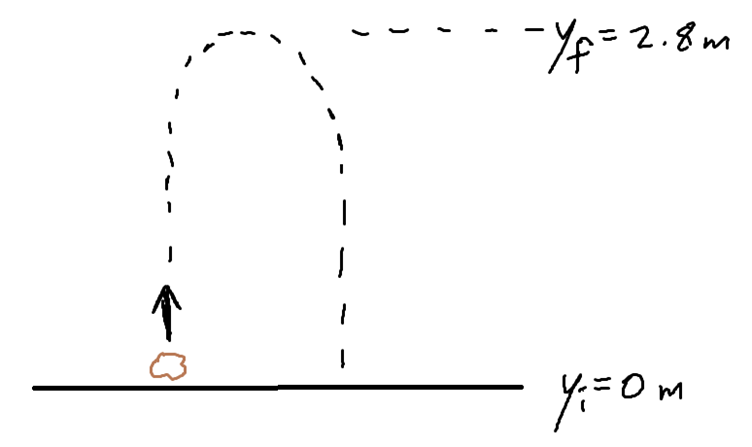

Let's begin by drawing a simple diagram that provides a visual description of what's happening:

At maximum height, or $y_f = 2.8$m, the velocity is zero, $v_f = 0m.s^{-1}$.

The initial position is set to zero, $y_i = 0m$.

Acceleration is due to gravity, so $a = g = -9.8m.s^{-2}$ (negative for downward direction). Let's calculate the initial velocity, ${v_i}$. We can use equation (8): \begin{align*} v_f^2 &= v_i^2 + 2a(y_f - y_i) \\ \implies v_i^2 &= v_f^2 - 2a(y_f - y_i) \\ \implies v_i &= \sqrt{v_f^2 - 2a(y_f - y_i)} \\ &= \sqrt{(0m.s^{-1})^2 - (2)(-9.8m.s^{-2})(2.8m - 0)} \\ &= 7.41 m.s^{-1} \end{align*} Now that we've calculated the initial velocity, we can use equation (4) to determine the time it takes for the stone to reach maximum height: \begin{align*} v_f &= v_i + gt_{\text{top}} \\ \implies t_{\text{top}} &= \frac{v_f - v_i}{g} \\ \implies t_{\text{top}} &= \frac{0 - 7.41m.s^{-1}}{-9.8m.s^{-2}} \\ &= 0.756s \end{align*} The time taken to return from maximum height back to the ground is the same as the time taken to get to the top, so the total time is calculated as \begin{align*} t &= t_{\text{top}} + t_{\text{bottom}} \\ &= 0.756s + 0.756s \\ &= 1.51s \end{align*}

References

- Douglas C. Giancoli, Physics: Principles with Applications - Second Edition, Prentice-Hall International Editions, 1985